Badass Larp Talk #11: To Live and Die In A LARP

One of the most telling decisions a game designer can make is how to handle character death; in many ways, how characters permanently exit play is just as important as how the game is played. It tells players the margin of error they’re looking at when it comes to characters failing, and also determines a number of other factors that might not be as obvious, such as the impact of player versus player (pvp) conflict.

So let’s break it down by the three main types of death systems and see what shakes out, shall we?

Single Death Systems (SDS)

Outside of certain high fantasy and super advanced science fiction settings, single death systems are the norm for a lot of games. Also known as “real life rules” since they closely mirror our actual human experience, SDS games have arguably the lowest margin of error of any system formulation, where even just one unlucky rules interaction could send a much beloved and long-played character out of the story for good. From a bookkeeping perspective, they’re probably the simplest of all the death systems out there, as when a character dies there isn’t much else to do but chalk up another strike mark and talk to the player about what they’d like to play next. Or at least that’s what it might seem like, except that it trades some simplicity in the aftermath for some complications before the fact, and you’d better be careful to figure out how you plan on handling them if you don’t want to get blindsided by some of the unexpected parts.

Advantage: High Stakes

Needless to say, when there are no come-backs, players have to take risks accordingly. Operating without a safety net in the event of foul play or catastrophe can be a rather brutal learning curve for some players, but it certainly means adds a heavy dose of excitement and tension any time lives are on the line. Given that most of my early larp experience was with the World of Darkness setting, a fundamentally SDS setting (though most characters had a lot of possible “outs” with their powers), I have to say it was hard to adjust to other systems at first. I wondered how tense it could be when you had multiple or even functionally infinite lives, because even though I hated the idea sometimes, there was a lot to be said in favor of how much it added to those dangerous moments, not to mention how much greater the triumph was when we walked away and a hated enemy did not.

Drawback: Wait, No! That’s Bullshit!

At the same time, SDS games require a lot of staff attention to make sure that they’re not being exploited, on several levels. For one thing, SDS games often have to contend with a higher rate of cheating than other systems, simply because when faced with losing a beloved character even normally honest players will often be sorely tempted to fold, spindle, mutilate or outright ignore the rules, especially if they feel it isn’t how their character is “supposed” to meet their end. Along the same lines, staff needs to decide in advance how to handle it if some players decide they’re bored and feel like killing other peoples’ characters just for something to do. Sad to say, this does happen, and it can be a major problem for games.

Possible Fix: Death’s Door Mechanic

To cope, a number of games have started adopting “delayed death” mechanics where a character is functionally removed from play – as in, cannot take any actions that involve rules or skill use of any kind, and sometimes are forbidden to talk about certain subjects (such as naming their killer in pvp situations) – but do not actually expire until the player wishes it or the end of a set period of time, which is usually but not always the session wherein the killing blow was inflicted. In effect, the character lingers long enough on death’s door to say some goodbyes and allow the player some chance to wrap up some business to allow for more closure in the face of sudden and permanent character loss, but without taking all the sting out of SDS games or making pvp killing impossible to conduct anonymously.

Unlimited Death Systems (UDS)

At the other end of the spectrum are UDS games, where death goes from being a character-ending experience to something more like a timeout or an inconvenience. (For the record, many supposedly UDS games actually have a handful of situations or conditions that can permanently remove characters, but these are often special plot directed circumstances and not elements that are casually encountered, so I’m setting them aside for this discussions.) The very first boffer LARP I ever played was a UDS game, and so I didn’t realize how uncommon it was until I started checking out other games and saw only a handful of other games I looked up online shared a similar philosophy.

Advantage: Risk Taking

One thing that players who don’t have experience in a UDS game often overlook is that – by its nature – UDS games encourage players to take risks. When you don’t have to worry about a single bad decision taking away your character, it’s a lot easier to dive in and take your chances in situations as compared to characters who get only one or two deaths. When we began at my first boffer larp – a place where resurrection took only 5 minutes – my brother and I became known for dying constantly. At my first event, I managed to die four times in half an hour, simply because I kept throwing myself in the thick of things for the fun of it. I was underpowered, couldn’t fight for crap and squishy as hell compared to the bad guys, but who cares? I was trying all kinds of tricks – flanking attacks, playing dead (not hard when you become known for getting killed), pretending to be under enemy control – and more importantly I was enjoying myself even when I failed and got ganked. A UDS game encourages players to take chances by removing one of the main reasons players play it safe in the first place, and as a result it feels very friendly as a learning and immersion environment.

Drawback: The Revolving Door

Of course, the same carefree abandon of those early games eventually wears off for most players, and at this point your game can have a serious problem: apathy. While permanent character loss can rip beloved characters away from people, not to mention make them grumble about hundreds of dollars of props and costuming becoming useless, it does serve a valuable motivating purpose, not to mention add tension to situations. For newer, less powerful characters, death is still something of a deterrent in a UDS game, if only because it can happen to them more easily and thus mean they have to be careful if they don’t want to miss out on crucial scenes due to being dead (or raised as enemy undead, or whatever). For more powerful characters, however, almost all the inherent risk is gone – they don’t fear most enemies because they’re seasoned players and have powers to back up their experience, and they don’t fear death because they know it’s temporary and have gotten used to it. Death is annoying and tiresome instead of frightening and traumatic, and that’s a major shift in attitude to play out. Worse still, if villains enjoy the same immortality, it can be hard to feel as though you ever get to defeat them. If you kill them, they just come back later; if you capture them and they escape, you start feeling much the same way.

Drawback: Power Scaling

When characters never have to be removed from play (at least until the player chooses to do so), a UDS game has to take a long, hard look at what’s going to happen down the line when those characters have been at game for years and accumulated huge amounts of experience points, fantastic gear, etc. Unlike other death systems, where there’s a strong chance that player characters will either die off or choose to retire due to impending doom, in a UDS game there’s no cap except player boredom regarding how long a character can gain experience, which means that if you have characters who choose to stay active for long periods of time you can have significantly unbalanced power levels in your player population. For this reason many UDS and even some LDS games bestow experience on a sliding scale, granting more early to encourage player growth and interest and then scaling back over time so that long-running characters advance much more slowly. Whatever the game chooses, though, this is a factor to be seriously considered in all but the most short term games.

Possible Fixes: Giving A Damn (Players) & Alternative Approaches (Staff)

Normally I don’t like to lay blame on players for system elements, but generally speaking the revolving door problem becomes a problem mostly because of roleplay habits and not staff issues (though stories that make light of the revolving door certainly don’t help). Simply put, you have to remember that even if your character is aware that death is temporary for some people in her world, that doesn’t mean it isn’t painful and unpleasant to experience, which should be roleplayed accordingly. It might also inspire her to fight harder on behalf of those who don’t share her functional immortality, as is the case in many fantasy settings, where heroes are repeatedly raised back to life but humble farmers fall once and stay dead. In short, you have to remember that even if you the player know death is little more than a time out, your character still experiences it as a much more intense, disturbing experience. And if she doesn’t, what does that say about how callous her attitude has become about life and death …?

Of course, staff isn’t totally off the hook here. If you run a UDS game, you need to think of other ways to threaten players and resolve conflicts that don’t encourage the negative aspects of this system. While killing the big bad guy is a nice exclamation point in many game systems, if the bad guy is just going to come back to life again later, you need to make sure the players don’t feel cheated or that their actions are pointless. (Maybe it takes them a certain amount of time to return, or players can perform certain dangerous rites or use rare technologies that prevent resurrection in order to keep particularly nasty villains from coming back.) Also, just because players can return to life functionally forever doesn’t mean that it has to be wasted time for their characters – have staff members narrate experience between life and death when possible, showing an afterlife experience full of strange visions, comforting loved ones long lost, villains waiting for revenge or whatever else the world dictates. A really ambitious staff could use the time between death and resurrection to sow clues about ongoing plots, or even run whole story arcs in the time between life and death, possibly even requiring players to deliberately die to run special “flatliners” adventures in the sinister and eerie underworld from time to time …

Limited Death Systems (LDS)

As the term implies, LDS games bridge the gap between the two worlds – players have more than one life but not an infinite amount, and so it enjoys some of the benefits of both while downplaying the drawbacks a bit in process.

Advantage/Drawback: The Best of Times, The Worst of Times

Death is still a source of great tension in LDS games, since you don’t have an infinite number of “respawns” to fall back on, but you can also take comfort in knowing that your first fatal mistake won’t be your last either. In some games the players know the exact number of lives they have, while others keep them secret in a staff database of some kind; generally I prefer that players have a way of knowing how many lives they have, even if the character does not, because it lets them make decisions about retirement and wrapping up stories that they wouldn’t have otherwise, but there are certainly excellent roleplaying arguments in favor of the mystery and uncertainty of not knowing either.

One of my favorite compromises, in fact, comes from the absolutely superb roleplayers at the NJ fantasy larp Nocturne, where players don’t know how many lives they have … until they are resurrected into their last lifetime, which is accompanied by a brilliant display of IC pyrotechnics that signals to player and character alike “this is your last life, use it well.” I always thought that balanced the two elements very well – the player doesn’t know exactly how long their character has left until near the very end, so they have to play cautiously as they might not have more than just the one life left, but when the actual end is near, both player and character are clearly informed and can plan and roleplay accordingly. It’s a brilliant way to handle the LDS mechanics, and I’ve always thought it was a very elegant solution.

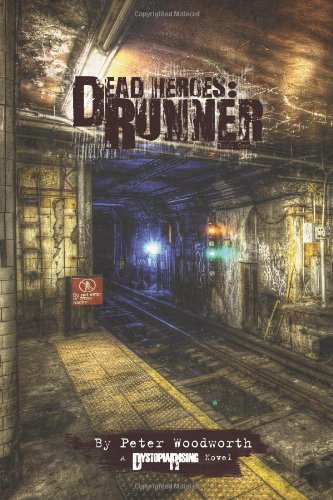

Of course, there are other twists to the LDS model that are worth investigating too. Post-zombie-apocalypse madhouse Dystopia Rising uses an LDS mechanic where players know up front exactly how many “lives” their character will have before the zombie infection claims them for good. (Generally speaking, the lower the number a particular character type has, the stronger their starting “genetics” and native skills are, which is a nice bit of game balance to accompany the LDS mechanics.) Technically speaking, there’s no way to get back an “Infection Point” (the term for lives), as losing them to death represents your character slowly succumbing to the zombie plague … however, there are a few tricks you can try if you’re desperate and fading fast. Only one of them is listed in the rulebook – and even then it’s a rare and dangerous skill known only by a few decidedly creepy people – so if that doesn’t work for you, you’d better get creative and dig into some intense roleplaying and exhaustive searching. Having other ways to extend a character’s lifespan hidden in the dark reaches of the setting is a great way to encourage exploration and roleplaying, and that’s before you actually have to consider the moral and philosophical costs of some of these potential “cures” …

The one major thing to consider when crafting an LDS game, in fact, is whether the number of lives that players are given is set in stone, or if it can be tweaked during play. If it is unchangeable, you need to make sure everyone knows it, and make sure that rule is never bent unless you want the players who didn’t get that favor to riot on you. If it can be changed – if players can acquire more lives, “buy back” lives lost, or some combination of both – then you need to very carefully consider how they can go about what might be described as the most important mechanic in your system. If you make it too easy, you’ve essentially made a UDS game and death loses all tension; if you make it a matter of raw in-game power, you’re sending newer players a message about how valued their characters are in your system, at least compared to veteran characters; if you establish it as a perk of belonging to particular faiths or organizations, you make it difficult for players to resist joining if they want to continue playing, and so on. My recommendation? Talk it over with the staff and your founding players, and make sure that the answer also reinforces your setting and its lore.

Now Pay the Ferryman, Son

So what sort of conclusions are to be drawn from examining these mechanics? Having played extensively in a variety of games using all three systems over the years, I can say that it’s not a question of right or wrong, as some game design adherents might have you believe. I hope I’ve been able to show that all of them have powerful advantages for staff members to use in order to craft excellent stories, and factors that players should bear in mind as they approach playing in different death systems. I’ve also tried to raise a few of the disadvantages I’ve seen in the different systems over the years, as well as possible fixes – I’m not going to pretend those are the only problems with those systems or that my fixes will work in every instance, I’m just hoping to point folks in the right direction to anticipate problems and formulate solutions that work for their games.

Because in my experience, death systems are one thing that are nearly universal in gaming, and yet many players and even quite a few staff members often don’t stop and think about the implications of a particular system on their setting or their characters. Which is a shame, because understanding what death means and how it works in the game is an important part of understanding what kind of heroes exist in your setting, the challenges they’re up against, and the risks that make their choices matter.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep, my sweets.

Take the long way home.

—————————————————————————-

Badass LARP Talk is a semi-regular advice series for gamers who enjoy being other people as a hobby. Like what you read? Click on the BLT or Badass LARP Talk tag on this entry to find others in the series, follow me on Twitter @WriterPete, or subscribe to the blog for future updates!

Leave a comment